|

|

Additional information taken from various sources, as noted--

|

Like most other "new lands", the land that

became Texas was explored and settled first from the coastline on the Gulf of

Mexico and then overland from both East and West by treasure-seekers, the

clergy, the military, the political opportunists and the land-hungry settlers.

The strategic location of Texas made it a sought-after territory by nations

interested in colonizing the North American continent. To appreciate the

significance of the El Camino Real that bisected this strategic real-estate, one

must give at least a cursory glance at the history of Texas.

It is impossible to establish the date of the beginning of the road that is perhaps the oldest regularly traveled in what is now the United States. It ran from Mexico City, Mexico through San Antonio, Texas to Natchitoches, Louisiana and on to San Augustine, Florida. The network of roads that connected Spanish colonial territories, known as Caminos Reales or Royal Roads or Kings Highways, was a vast and interconnected system of roads and paths. To the Spanish, El Camino Real was a road traveled for the Sovereign to colonize, Christianize and seek riches for the Crown. Before European explorers, missionaries, soldiers and traders, the roads had been carved out by Native Americans. The roads connected watering places, military installations, Missions and trading outposts. With the Franciscan Missions, the Presidio (military) and the river, San Antonio became a hub for many of the colonial roads. The Camino de Los Tejas or Old San Antonio Road or Old Spanish Trail linked the Presidio San Juan Bautista del Norte on the Rio Grande going across Texas to Los Adaes on the Sabine River on the border with Louisiana. It is reasonable to assume the "the Road" was the basis for the development of the Spanish Mission system as early as 1660-1665. By the time the Spanish government built a mission settlement at San Antonio in 1720, the Mission San Jose was considered the strongest for military purposes as well as the most architecturally ornate of the five missions built there. One cannot investigate the significance of "the Road' without looking at some of the history of the area and how the development of the State and the development of "the Road" interacted with each other and were influenced by economic, social, political and religious influences which were in flux for a period of centuries. Slightly more than a decade after the exploration by Christopher Columbus, various European powers followed up on his initial discovery with numerous expeditions. The Spanish did not limit their explorations to the southern Caribbean area. However through approximately the first half of the 17th century, the territory north of the Gulf of Mexico held little interest for the Spanish Crown. On the other hand, French activity was in marked contrast to the Spanish. By 1682, the French explorer, Rene Robert Chevelier Sieur de La Salle had explored the Mississippi River and claimed both it and the land it drained for the French Crown. In the meantime, both the British and the Dutch had established colonies on the Atlantic Coast as the Spaniards had in Florida. The stage was set for conflict over both the territory as well as the boundaries of same. The Italian cartographer Vincenzo Mario Coronelli produced a series of maps for the explorations of La Salle in 1695. He depicted the course of the Mississippi River as explored by La Salle but he placed the mouth hundreds of miles too far west--nearer the mouth of the Rio Grande. This error set the stage for serious confrontation in Texas. La Salle returned to France after exploring the Mississippi River and received permission to colonize the area of the mouth on the Gulf of Mexico. Instead, he ended up in Texas and died there in 1687-88. Nonetheless, this effort forced Spain to become interested in this territory in order to create a barrier to further French colonization inland from the Gulf of Mexico. The Spanish responded to the challenge and took advantage of the opportunity. In 1686, The Spanish Viceroy ordered the first of several expeditions under the leadership of Captain Alonso de Leon. In 1690, de Leon made his last trip to Texas with Fray Damian Massanet to establish a permanent mission in Texas to serve as a deterrent to French aggression. They established San Francisco de las Tejas on the Nueces River thereby marking the beginning of Spanish missionary and colonial activity in Texas which lasted more than a century and left a permanent stamp on the character of Texas. For Fray Damien, the dream of building missions across the Tejas territory began prior to 1690 and for 10 years he pushed his way from Mexico north and east. Captain de Leon maintained that the territory could be held against the French threat by a line of forts. The Franciscan Friar went back to Mexico to insist that a line of missions be built instead. The Church prevailed and in the Spring of 1691, Fray Damien set out with the first provisional governor, Domingo Terran de los Rios, to blaze the El Camino Real, the route for the intended missions. Fray Damien, Rios and their party traveled the Camino Real from below Eagle Pass to San Antonio. A rift between priest and soldier deepened and finally broke as the group traveled past San Marcos to the Colorado River crossing near Bastrop when supplies did not arrive. There was also word of trouble with the Indians at Mission Tejas in east Texas as well logistical problems trying to supply the missions from settlements in northern Mexico. In 1693, Fray Damien, along with a younger priest, Fray Francisco Hidalgo, was forced to leave Mission Tejas. It was left to Fray Francisco over the next twenty years plus to see the line of missions across Texas completed. In the meantime, the French had continued to explore Louisiana. In an effort to establish trade with both the Spanish and the Indians to their west, Louis Juchereau de St. Denis was commissioned in 1713 to open an overland route. The Duke of Linares, Viceroy of Mexico, offered St. Denis second in command and a guide for a Spanish expedition to re-establish the east Texas missions. Fray Francisco had warned the Viceroy that Spain must re-establish the missions and colonize the land or lose Texas to France. In 1714, St. Denis crossed Texas to the presidio and Mission San Juan Bautista on the Rio Grande. In 1716, Domingo Ramon, St. Denis and their party of seven priests and sixty soldiers set out to cross the Rio Grande on the Camino Real toward San Pedro Springs and beyond to Nacogdoches, where St. Denis lived out his life as a wealthy trader. The French had encouraged this venture because the new missions would depend on French Louisiana for trade. In 1719, following a conflict between Spain and France, the East Texas Missions were briefly abandoned. In 1721, the Viceroy commanded Jospeh de Azlor the Marquis de San Miguel de Aguayo to go to East Texas and re-establish Spanish control. Spain had begun its' colonization of Texas when 15 families from the Canary Islands began platting their township according to a map drawn by the Marquis de Aguayo. The Spanish Crown established 36 missions in Texas. Five of these were built along the banks of the San Antonio River all within a 12 mile radius of the city as it is today. Founded by the prominent Franciscan Missionary Fray Antonio Margil de Jesus and named for St. Joseph and the Marquis de San Miguel de Aguayo, Mission San Jose y San Miguel de Aguayo was established in 1720 as a center for cultural and religious training. Known as the "Queen of the Missions", the entire compound has been restored and designated both a National and a State Historic Site. Mission San Jose along with Missions San Francisco de la Espada, Nuestra Senora de la Purisima Concepcion and San Juan Capistrano make up the Historic Mission Trail and each is still an active church with regularly scheduled services. By 1731, the Presidio San Antonio de Bexar had been established. The Marquis de San Miguel de Aguayo, a tough, incisive and smart soldier, had built the Presidio because of French pressure from the east. Throughout the eighteenth century, the Spanish remained driven by the defense of Texas against French and British interests. The Marquis de Aguayo's work was the high point of Spanish colonization in the eighteenth century. The Presidio San Antonio de Bexar guarded the nearby Mission San Antonio de Valero which became secularized in 1793. Thereafter, it was used for various purposes including, in the 1820's, housing the soldiers from El Pueblo del Alamo de Parras de Mexico. The Governor of Coahuila Mexico, Martin de Alarcon, provided a mission half-way between San Francisco de los Tejas and San Juan Bautista. That mission, San Antonio de Valero, on the San Antonio River, was established in 1718 by Franciscan Missionary Fray Antonio San Beunaventura Olivares. It became the most important Spanish post in Texas. It was later to be the site of a pivotal battle in the Texas war for independence from Mexico. It remains today celebrated in music and film and is one of the nation's top tourist attractions--for many years known as The Alamo. As the French and Indian War was drawing to a close, the French realized they were beaten. To prevent Louisiana from falling under British control, France ceded it to Spain in 1762 under the provisions in the Treaty of Fontainebleau which was confirmed by the Treaty of Paris in 1763. As a result, the East Texas Missions were no longer needed as a buffer against French Louisiana. Athanase de Mezieres was a French nobleman who was a contemporary of Washington, Jefferson and Patrick Henry. He was a soldier who crisscrossed Texas from the Sabine River to San Antonio for 10 years. He had come to Louisiana as a young man and married the daughter of St. Denis. When France ceded Louisiana to Spain, Spain commissioned Mezieres territorial Lieutenant Governor for the Sabine frontier. In 1779, the King of Spain proclaimed Mezieres Governor of Texas but he died before taking office. His last reports foresaw Texas as an empire occupied by Anglo settlers from the East. After 1763, even though the British were geographically positioned to challenge the Spanish, they were busy with colonial uprisings. The American Revolution, which was brought to an end with the second Treaty of Paris approximately twenty years following the first, established the new American Republic as Spain's neighbor across the Mississippi River. But by the turn of the century, Spain ceded Louisiana back to France as a provision in the Treaty of San Ildifonso. By 1803, Napoleon sold Louisiana to the United States. This still left Spain with Louisiana's western boundary questions which now had to be negotiated with the United States. The expeditions from the United States into their new territory with disputed boundaries alarmed the Spanish as did the independent immigration of American frontiersmen. Eventually, an agreement, honored by both sides for years, set the Sabine River as the boundary line. In 1810, the first significant internal threat against Spain's control of Mexico -- the Hidalgo Revolt -- though easily put down, marked the beginnings of disorders that would occur over the next several years. Diplomatic efforts finally settled the boundary between Spain and the United States in 1819. That was the Adams-Onis Treaty. To secure Spanish concessions in Florida, the United States accepted the Louisiana boundary as the Sabine River which was well east of its original claim. This resolution, which surrendered territory that had been believed to be part of Louisiana, encouraged attempts to "restore" the Texas territory to the United States. Coinciding with the influx of Anglo settlement into Texas in 1821, Mexico revolted against Spain and became independent. The Impressarios, who had been granted colonization contracts, had been so successful in attracting Americans to Texas that by 1828, Mexico was alarmed that Texas was becoming completely Americanized. Manual de Mier y Teran was sent to investigate. He crossed Texas and when he reached Nacogdoches was alarmed to find it thoroughly Americanized. His report contained recommendations for extending Mexican control over the province. These recommendations were incorporated into law in 1830 which established Mexican garrisons across Texas and prohibited further immigration of Americans. The colonists resentment of these provisions eventually led to war in 1836 which had as a result the formation of the Republic of Texas. In 1836, the voters in Texas ratified their constitution, elected government officers and voted in favor of annexation to the United States. Though it took the better part of a decade to finalize, by 1845 the United States took action and Texas was admitted to the Union. Annexation was reviewed by Mexico as a hostile act. In May 1846 Mexican troops crossed the Rio Grande which they did not recognize as the international boundary and thus the U.S.-Mexican War began. It ended in 1848 with the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo which set the border between Mexico and Texas as the Rio Grande.

Martin, J. C. and Martin, R. S.: Maps of

Texas and the Southwest 1513-1900; Amon Carter Museum; University of New

Mexico Press, 1984.

|

|

|

|

In 1915, the Texas Society, Daughters of the American Revolution working with the Texas Legislature, arranged for the survey of the Old San Antonio Road from Louisiana to the Rio Grande and granite makers to be placed at approximately 5 mile intervals. The history of the Texas DAR and the 1918 TSDAR "Proceedings" note how this came about. In 1911, Mrs. Lipscomb (Claudia W.) Norvell, a Texas DAR, was attending the DAR Continental Congress (annual convention) in Washington D.C. when a delegate from Missouri declared that the Santa Fe Trail was the oldest in the United States. Mrs. Norvell took exception to that remark and countered with the El Camino Real having been in use since (recorded) 1691 when Domingo Teran de los Rio traveled the route to the Spanish Missions in Tejas (Texas). In November 1911, meeting in Galveston, the Texas DAR selected Mrs. Norvell to oversee placement of pink granite markers at approximately 5 mile intervals along the Real. The location of the road was verified by old Spanish land grants and other land records. A surveyor, V.N. Zivley was hired to survey and mark the route. The Texas DAR contributed $10,544 with an additional $2,500 coming from the members and the State Legislature appropriated $8,000 to assist in this most worthy endeavor. The railroads contracted at 1/2 the regular portage rate to transport the granite markers to their designated locations. On December 27 of that year, a contract was let to Mr. A. L. Gooch for the sum of $4,300 for 123 markers installed at the stakes left by Zivley. Mr. Gooch placed 118 markers from the Sabine River to the town of Cattarina "--but owing to the condition of the country west of Cattarina, it was utterly impossible to set the remaining 5 markers". The remaining markers were installed by local craftsmen. According to W. E. Dunn, a University of Texas archivist, the marking of the El Camino Real is the most significant of the work undertaken by the Texas DAR. The Texas DAR presented the Markers to the State of Texas in a ceremony on March 2, 1918 in San Pedro Park in San Antonio. Mrs. Norvell, Texas State Regent 1918-1920, who had been the state chairman for this ambitious project -- --presented to the State of Texas, a surveyed, marked and inspected trail-

that commemorates a life history of a people lost for more than a century; it has been located by an archivist from the Spanish explorer's diaries, in their route across Texas, as Camino Real, Royal Highway; and from the American surveys calling for the old San Antonio Road, it was identified as one and the same road, as the Americans had blazed the Camino Real or Royal Highway into the Old San Antonio Road. Famed as a monument to the ages of Texas history--a permanent chain of one hundred and twenty-three granite stones are marking an empire from the east to the west borders of the state, to perpetuate man's struggle for advancement, from which has sprung our civilization today.

An undertaking begun eight years ago, the marking of a continental trail across Texas, the great Southwest, through the efforts of the State Chairman of Old Trails Committee, Mrs. Lipscomb Norvell, who suggested the perpetuation as a definite work of our own by the Texas DAR, the rediscovering and marking of its historic highway, Camino Real, or Old San Antonio Road, is the most significant of all the work undertaken and completed by the Daughters of the American Revolution in Texas. …

The movement was commemorated on March 2, Independence Day of Texas, as a combined chapter offering to the courage, bravery, valor, self-sacrifice, suffering and joy of the American pioneer, who in the early days passed over this trail through Texas into that great unknown Southwest. …

…Rejoining in the completion of a patriotic task, which has enlisted the untiring zeal of the Chairman of the Daughters in Texas, the two local Chapters, the San Antonio de Bexar and the Alamo, united in paying tribute to their State Regent at a luncheon at the St. Anthony Hotel on March 1st. In eloquent speeches the final realization of their ideals, and those of the Texas Pioneer who blazed the trail of the King's Highway into the Old Spanish Road at San Antonio across the wilderness and plains of the Lone Star State, were eulogized.

The Daughters presented this historic trail to the State in an impressive ceremony on March 2nd, at San Pedro Park. The presentation of the surveyed, marked and inspected trail Camino Real, King's Highway, or the Old San Antonio Road, was made to the State of Texas on that afternoon by the Daughters of the American Revolution. The historic trail was the natural highway for hundreds of Indians and Spanish explorers and Fathers, Mexican settlers and soldiers, and finally Americans, was a gift to Texas on the 84th anniversary of the declaration of her independence.

The speakers of the occasion included Mrs. Lipscomb Norvell, State Regent of the DAR; Mrs. James Lowry Smith, Vice President General of Texas; staff officers and members of the DAR and a number of local historical and civic organizations.

The granite marker, one of the 123 which designate the course of the old trail, was placed in the western side of San Pedro Park. Here under the boughs of giant trees the unveiling was held and the presentation of the road made to the State.

A large canvas pointed map of Texas, size 18 by 18 feet, was framed at the back of the grandstand, erected for the occasion, draped in bunting, with the road drawn in red, and the markers painted black, showing the route of road and the markers where placed across the state.

After the invocation was pronounced by Dr. Bertrand Stevens, rector of St. Mark's Church, were several military features, including music by the Army post band, bugle calls and a unison recitation of the soldier's allegiance to the flag. Greetings were extended by Major Bell, representing the city; S. E. Cornelius of the Chamber of Commerce, and regents of the local DAR chapters. Other features of the program--an address by Mrs. A. B. Looscan, president of the Texas Historical Society, the three generals of the San Antonio army posts, the presentation of the surveyed, marked and inspected road by Mrs. Lipscomb Norvell, and the acceptance of the State was voiced by Judge Norman G. Kittrell, of Austin.

At the close of the program an exquisite silver service was presented to Mrs. Norvell by the chapters of the state, for her loyalty to the cause, in bringing this patriotic undertaking to a close.

[This account was taken from The Texas State History of the Daughters of the American Revolution published in 1929, p. 51-54] |

![]()

|

Each marker bears the inscription: Kings Highway, Camino Real, Old San Antonio Road, marked by the Daughters of the American Revolution and the State of Texas, A.D. 1918. In 1929, the Texas Legislature declared the Zivley surveyed Old San Antonio Road to be one of the Historic Trails of Texas. |

![]()

|

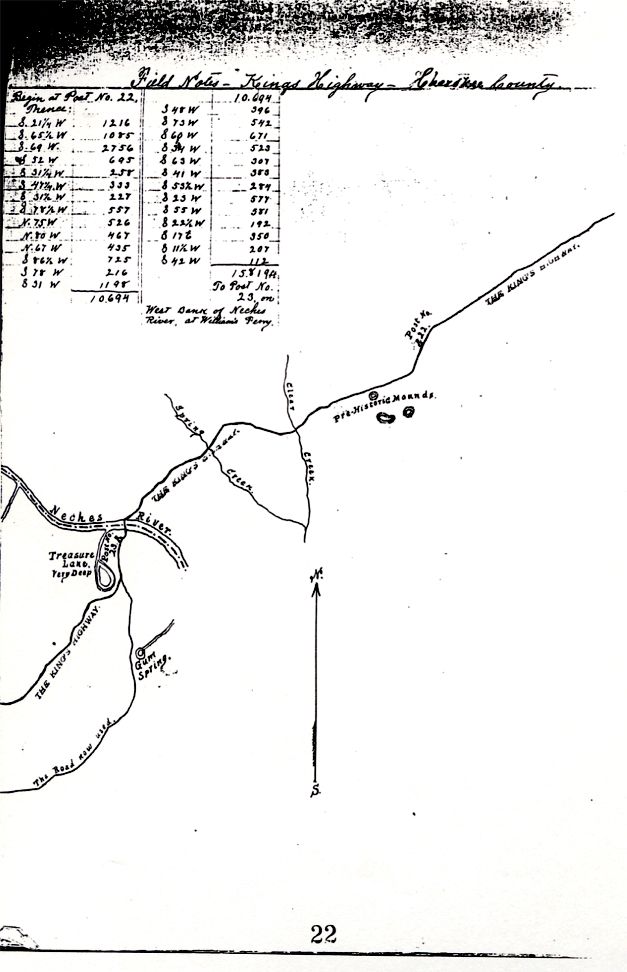

These are the observations of V. Z. Zivley that precede his drawings. [note: The reader is reminded that what appears below are Mr. Zivley's hand-written field notes--which were just that--his "notes" to himself as he surveyed the land--not a "finished" document. The text has not been edited. The account is from Mr. Zivley's working notebook, carried across Texas in 1915 and 1916. It is not in good condition. ed.] In East Texas, that is, from the initial point to the crossing of the Colorado river at Bastrop, the King's Highway, while in many places has been abandoned and entirely obliterated, was very definitely located by the field Notes of land surveys made in the early years of the last century. These surveys were either bounded on one side by the old road, or if they crossed it the course and distance from the nearest corner to the said crossing was in most instances stated, so that the relocation of the road in that part of the State was only a question of time and labor.

From Bastrop to San Antonio there was little to guide me except tradition and the remaining evidence of the road to be found on the ground…

…I have given this work the very best effort of which I am capable, I measured every meander, every deflection of the old road as carefully as I ever measured a line for a proposed railroad, and I have reproduced the road on the Map just as I found it on the ground. In the Field Notes and Map I have endeavored to show every object either natural or artificial near which the Road passes, that would tend to permanently fix its location. In putting up the markers, in a few instances the distance between them is somewhat in excess of five miles but was covered in that deviation from instructions by what I think good judgment--for instance where the measured five miles would have necessitated the placing of a post in the midst of a cultivated field, I either stopped short of the instructed distance or went a few hundred feet beyond, in order to place the marker where it would be least likely to be molested…

…From San Antonio to the Rio Grande or vise versa from the Rio Grande to San Antonio, about the only guide I had was the diary of Morfi, a very learned and observant Spanish Priest who traveled the King's Highway in December 1778 from Presidio Rio Grande to the old Missions at San Antonio and to that old Padre, though I am a Protestant of the most ultra blue stocking type, I want to doff my hat, as the most accurate artist in words of a country traversed that I have ever met--in books. Every place he mentioned, every object of interest, I found just as described by him in that brief diary. His only inaccuracy was in the distance stated between given points, invariably the distance given by him was greater than that given by the steel tape. But I picture him as a scholarly devout man of fragile physique and wearied as he was by the days travel "y muchas inflexions inutiles" how natural for him to over estimate distance.

I am well aware that a work of this kind should be entirely self-explanatory, but owing to adverse conditions and some very misleading data that was furnished me, I have been compelled to perpetuate a seeming inconsistency. There were only one hundred and twenty-three (123) posts or markers placed by me between the Sabine River and the Rio Grande, and the Posts should have been numbered consecutively from beginning to end, but as will be seen the Post at Paso de Francia is numbered 128 while in La Salle County there is a skip from Post No. 102 to Post No. 108, which occurred in this way: As I went South after putting up marker No. 102 I failed to find or notice the Presidio Road turning to the right and continued to follow and survey the Laredo Road to old Fort Ewell on the Nueces River. The map I had showed the King's Highway went in that direction and after crossing the Nueces at Fort Ewell turned almost to the West and crossed the I.& G. N. R. R. (International and Great Northern Railroad) near Artesia Wells. When I reached Fort Ewell and made a thorough examination of the crossing there I became convinced that I had been misled and found that no road crossing the Nueces there had ever turned to the right in the direction of Artesia Wells from the fact that the country is so rough and broken that a Wolf could hardly get over it. I then spent several days in exploring the river for a crossing above Fort Ewell and at the Black Ranch, about midway between Fort Ewell and Cotulla, found an old ford from which a road led in a westerly direction--but the ford did not at all fit the description of the King's Highway crossing as contained in the diary of Morfi relating a cross over this road in December 1778. Disheartened and almost discouraged, I decided to go by the most direct traveled route to Paso de Francia on the Rio Grande, pick up the road there, follow it as described in the Morfi Diary back to its intersection with the road I had surveyed. This I did, but when I reached the Rio Grande, I had to guess at the distance and put up the Marker 128, which I afterwards found to be incorrect by almost twenty-five miles. I then carefully surveyed and measured the old Road from Paso de Francia this way, putting up markers where necessary and numbering them backwards that is from Nos. 128 to 127, to 126, etc, until I intersected the Road previously surveyed at Post No. 108. |

![]()

|

Below is a reproduction of a page from V. N. Zivley's field

notes showing his drawing and accompanying text and measurements. |

|

In 1936, the State Historian, Anne Johnston Ford, compiled a list with photographs, drawings and sketches of the various markers placed by DAR chapters across the state. This book was compiled as a "Contribution to the celebrations commemorating the State's Centennial Year". The following map has been reproduced from this book: |

|

The "call-out" captions were added to the image to call attention to the El Camino Real as so many other trails and markers are also shown on the map. The text from the book is found on page 12 and references the trail as well as a drawing of one of the markers and reads as follows: One hundred and twenty-three of these red granite boulders have been placed by the Texas DAR at intervals of five miles from Pendleton's Ferry on the Sabine to Eagle Pass in Maverick County to mark the approximate route of El Camino Real. This old road passed through or near San Augustine, Nacogdoches, Crockett, Bryan, Bastrop, San Antonio and Eagle Pass.

The route of El Camino Real was determined by Professor W. E. Dunn, an Archivist of the University of Texas. The earliest recorded crossing of Texas is that made by Solis in 1683. Another record shows that Morfi, a Spanish Missionary in 1778, traveled from Mexico to the Missions of San Antonio de Bexar and wrote of his route. The line of this route was used by Mexico as the designated northern and southern boundary for grants made to Texas colonists. There are no footnotes in the book to document these references. |

![]()

|

In 1929, the History of the Texas Society was compiled by Mrs. O. E. (Helen Dow) Baker, the State Historian. The 1929 History was reprinted in 1991 during the administration of Mrs. Thomas J. (Judith Hanner) Upchurch with Christene Jennings McKenzie, State Historian. On page 215 of the 1991 reprint, the reference to the King's Highway Markers reads: Dedication of King's Highway was held March 2, 1920 in San Pedro Park, where one of the 123 Texas granite markers stands. After nine years of undaunted efforts the two San Antonio chapters of the D.A.R., with the aid of our State Regent, Mrs. Lipscomb Norvell, were able to mark this Camino Real through Texas and Louisiana, aided by every member of the D.A.R. in the two states. [note: Now, the Daughters of the American Revolution use DAR as an abbreviation--without a period after each letter. However, periods are used after the letters in the History of the Texas Society D.A.R. ed.] In 1975, the Texas DAR published the History of the Texas Society commemorating the bi-centennial era in Texas. It updated the history of the Society from 1929 thru 1974. This book listed some of the El Camino Real Markers and their locations relative to nearby cities. |

![]()

|

Mrs. Ford, in the history of the Texas DAR that she compiled in 1936, mentioned the diary of the Spanish Missionary, Padre Juan Agustin Morfi written in 1777-1778, He wrote of his trip along the road from Mission San Juan Bautistas near Presidio Mexico to the Missions at San Antonio de Bexar. Surveyor, V. N. Zivley said of Padre Morfi, "I want to doff my hat to Morfi as the most accurate artist…that I have ever met in books. Every place he mentions, every object of interest, I found just as described by him in the diary." Mrs. Stegall, the Texas DAR Centennial State Regent has a photocopy of a typed transcription titled "Diary of Morfi". Unfortunately, there is no reference made to the original of this typed transcription or it's location. The text below is copied as it appears on the photocopy of the typed transcription. There is no notation regarding who made the translation from the original Spanish to English. It appears that the words in parenthesis may have been added by the typist as translation or explanation. Spelling, punctuation, etc. have been copied from the photocopy of the typed transcript. Diary of Padre Morfi, dated 1778

Dec. 24, 1778 we set out from Rio Grande, through some swamps and mesquite to the famous Rio Grande del Norte, two leagues E.N.E. to the crossing called French Ford. (446). It was not possible for us to arrive at the next water-hole which is the only one nearby for the horses, so it was necessary to camp on the opposite bank of the river, a pistol-shot's distance away.

Dec 25. I said mass before dawn. We set out at 7:30, over some hills, arid and rocky which form the opposite bank of the river, and entered a great plain of excellent land of good pasturage without water; and without seeing in any direction a single hill. At the termination of the plain (llano) we went down to a ravine of mesquite and other trees. The land is red, sandy. At the end of the ravine we found a large dry creek which preserves some pools of water all the year. It is called the Aguaje (waterhole) of San Ambrosia. Having passed this we saw another plain over which we traveled a league and a half to the spring of San Pedro. We did not stop, but continued over the same red sandy soil, and, at two o'clock arrived at the Aguaje of San Lorenzo, having traveled ten leagues East Northeast. This waterhole is a little pool of muddy water, surrounded by oaks (encinos) and other trees. From the ravine of San Ambrosio we saw many cacti and from San Pedro much verdolaga (purslain).

On the 26th we set out from San Lorenzo at 7:30, foggy, lasted until 10, when the sun came out. After ascending the hill (loma) near San Lorenzo we found a shrub we call in Spain una de gato (cat-claw). We took a turn towards the east in order to ascend a hill (loma) not seeing anywhere anything but gradual hills (lomerias suaves), one arising above the other in the shape of a canoe. On the top of it there is much loose and fine stone, which is not found in the ravines and meadows.

At eleven we arrived at the Aguaje of Santa Catarina. It is a little pool of water, somewhat cleaner than San Lorenzo. At two-thirty we arrived at the Pools of Barrera. The tents were placed on an elevation, having toward the East the Canoe (La Canoa). Ten leagues, five E.N.E., on East and four ENE.

On the 27th we set out at 8 o'clock, cold, and after a short distance, the hills (lomeria) continuing, we arrived at a thick wood of mesquite, nopal, etc., and near its end is the Aguaje of San Roque, where there is water in pools all the year. We did not stop, but went up the crest of the hill, which is the only rocky place (penasqueria) in the vicinity, although covered with undergrowth. From here the Nueces River can be seen and is not lost sight of until it is crossed. Descending the hill, the wood ends, and the lomerias (hills) continue to the Aguaje of La Romana, which is another pool two leagues from the preceding one, and not so abundant. We stopped here to warm ourselves. We set out through a little grove (bosquecito). The land changes to a cinnamon color. The last magueys are seen. Four leagues further and on the left of our road, there is a hill a little higher than the others around it, which is called La Cochina. On this side a few days before the Apaches killed some men. A little before this, a large number of wild horses crossed the road. We traveled two leagues over bare hills. Decended into a revine formed by the wood of La Cochina. The wood is very dense and divided into two parts by a little hill (lomita) which cuts it from North to South. We went another league and entered another ravine with grass, very high, and which the river floods in its rises. We passed this (the river) (or the ravine) at a swampy pool, ill smelling, and on the opposite bank at the entrance of a wood we camped. Eleven leagues, principal direction East Northeast, with many useless windings (muchas inflexions inutiles). This was the Nueces River they crossed. [It is not so noted, but this last sentence may have been an editorial remark added by the translator or typist]

On the 30th we set out at 8:15 over lomerias of nopal, mesquite, etc. Four leagues on we arrived at la Parrita, where in the midst of some oaks and mesquites there are some pools of bad water. We continued our journey without stopping, finding on both sides of the road clumps of live oaks, which look like so many villages (aldeas). Except for these groves, the hills are similar to the others we have passed, until about a league and a half beyond La Parrita, when with various trees the beautiful woods of Atascoso begins to announce itself, and begins after a half league more. We entered the wood, which was so dense that it scarcely afforded a path for the horses, and it was necessary to travel with great care in order not to be injured by the branches and trunks across the road. We went thru the wood for three leagues. It is formed of lomerias. At four o'clock we arrived at the Arroyo which is also called El Atascoso, having traveled nine leagues principally Northeast. The camp was placed in a level hollow of short extension and on the bank of a creek which in time of the dry season probably has a little more than a cubic vara of water, crystalline and very beautiful; but its ed (cauce) is full of leaves, etc. The wood is 40 varas long and 12 wide, and is composed of robles, encinos, alamas, etc. a few steps west of the camp and near the road we saw the skeletons of 203 bodies said to have been Apaches.

On the 31st we set out at 8:30 in the sleet, continuing through the thick wood as on yesterday. At a distance of five leagues is the ravine of La Magdalena and a little further on is that of Las Gallinas, both of which are dry creeks, and have water only in the rainy season. At two-thirds of the journey (Jornada), we changed our Northeasterly direction to one of due North. A little further on we came to some little cleared places, apparently intended for the site of a house. There is usually some water in a little lagoon which we now crossed dry. From this place the nature of the country changes. The sand, robles and encinos cease, and the woods of mesuite and cactus continue. We had not seen any nopal before this. A little further on from the cleared places and to the right of the road are some stones painted with crosses designating the limits of the first mission of Espada. It ends in a motte of 31 oaks (encinos) in the shape of a flower pot (Maceta). We ascended then a bare hill (loma). Down this, another mesquite grove begins and continues to the river. At 1:30, we arrived at the Medina River, boundary of the provine of Texas and Coahuila. We passed it dry, although there are pools of water at intervals. The banks of this river are so steep than on occasions it is necessary to ascend them on foot, suspended by a cord from the top. We passed them without this difficulty, however, and stopped on the opposite bank intending to spend the night. The countrymen with us killed a bear. We decided to go to Espada, and arrived there at 3:30 having traveled 11 leagues, 5 N.E. and 6 North. |

![]()

|

From Nacogdoches to San Antonio, the Camino

Real follows closely what is Texas Highway 21. From the Bexar County line, it

follows Nacogdoches Road to south Bexar County where the four restored Missions

are found on Mission Road. Past that point, there were a few state or county

roads/highways that developed further over the years. Travelers on "El Real" in

early years tended to move from one favorable camping place or watering hole to

the next. Today, many of the Markers in that part of the State are on private

ranches. In La Salle County, several of the Markers were moved from their

original sites to the right of way along State Highway 97. The State Highway had

been constructed to link the small communities and was approximately 2 miles or

so from the original Real. The Markers were moved in the 1950's in an effort to

preserve them for future generations. And so from untamed Tejas territory to dynamic State, six flags flew over the land -- Spain, France, Mexico, Republic of Texas, United States, Confederate and back to United States. From the French and Spanish soldiers, traders and missionaries to Sam Houston, Stephen F. Austin and all the other frontiersmen who traveled to Texas first to establish a Republic and then a new State, to Confederate soldiers and Union Reconstruction troops, to pioneers pushing still farther west, to European immigrants in the second half of the 19th century, El Camino Real has played a vital role in the settlement and development of Texas with each group contributing its own bit of cultural influence thus creating the unique character of the Lone Star State. As these Markers were photographed, sometimes described in relation to other buildings or natural elements, sometimes with GPS coordinates recorded, the information was compiled and given to Mrs. Stegall as the State Chairman for this endeavor. Additionally, more copies of the above, as well as the creation of the website, have been made for the Texas DAR in an effort to preserve the work that has been accomplished to date. There are still Markers that have not been photographed but this effort has not been abandoned. There are still Markers that have not been found. Many are in populated areas though highway construction may have been responsible for their dislocation. Mrs. Stegall's wish is that Chapters across the state will "adopt" a marker and check on it periodically to see if it needs cleaning, repairing, etc. Many of the Markers have been so "adopted". The goal is to photograph and record the GPS coordinates for those Markers that are on private property and not available to the general public. Who knows what the landscape will look like 75-100 years from now and this information could be valuable. This is an important, on-going project of the Texas DAR and deserves to be kept alive in the memory of the Society for future generations. On behalf of all the people who have contributed to the creation of the albums and the website, we hope that you enjoy your travel along the Old San Antonio Road/Kings Highway/El Camino Real. Just click on the county name buttons to travel from East (Sabine County on the border with Louisiana) to West (Maverick County on the border with Mexico) across the state as you follow in the footsteps of countless others who have traveled this road for over 300 years. |

|

The Counties are listed below in geographical order across Texas East to West. |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Click on the County name to go that County page. |

|

|